Idea Brunch #2 with Ted Rosenthal of TMR Capital (AI Edition)

Welcome to Sunday’s Idea Brunch, your interview series with great off-the-beaten-path investors. We are very excited to interview Ted Rosenthal!

Ted is currently the chief investment officer of TMR Capital, a long/short equity fund he launched in October 2019 shortly after graduating from Johns Hopkins University. TMR Capital has compounded at over 18% after fees since inception with no down years and Ted was previously featured on Idea Brunch back in July 2023.

Ted, thanks for doing Sunday’s Idea Brunch! Can you please tell readers a little more about your background and why you decided to launch TMR Capital? Any big updates since we last talked two years ago?

Thank you for having me on again!

I became interested in finance/investing when I was 12 years old. This was during the Great Financial Crisis of 2008, and my family was going through significant financial turmoil.

My brother and I moved countries to live in China, mostly because it was much cheaper. Before the GFC, we lived a much more comfortable life in Europe.

Everyone around me was talking about the housing bust and the economy, so I naturally became interested. I wanted to make sense of what was happening around me.

While I did not yet understand how to value companies or what P/E ratios meant, I intuitively felt that I should be buying some kind of asset after it had recently crashed.

The first stock I bought was Tencent because of my familiarity with the product. Everyone I knew in China was on it, and everybody my dad did business was also used it. We also lived a couple of blocks from their headquarters in Shenzhen.

I still have my shares to this day. I watched the stock go from $6 per share in 2012 to $100 per share in 2021.

As I watched my account size grow over the years, I became more and more interested in investing. I really got the investing bug in college and considered it a career. I read everything I could get my hands on. Fortunately, I stumbled upon Warren Buffett’s shareholder letters and was immediately taken with the value investment philosophy.

After studying Warren Buffett and Ben Graham, I did a mix of traditional value investing (low P/E, low P/B, etc…) but also kept my Tencent shares and looked for other quality compounders at a reasonable valuation.

What I found through my experience is that the traditional value investments had a pretty low hit rate. I would invest in a stock that is statistically cheap, but often the business would deteriorate even more than I and other market participants expected, resulting in a falling stock price. However, the earnings in many cases would also disappoint, and even fall, so in many cases, the P/E ratio never really declined much despite the lower stock price. In other words, the stock did not get cheaper as the price declined because the earnings also declined. This is a classic “value trap,” and there are a lot of those around.

Compounders, on the other hand, continue to get better and better each year. Their intrinsic value (free cash flow per share) increases each year. Every year, their moat gets wider and deeper. Therefore, as long as these compounders are purchased at a reasonable price, and the moat continues to get wider each year, the hit rate would be very high.

The trick is to buy them at a reasonable valuation. In many cases, the compounders are expensive. However, the stock market reliably experiences sharp drawdowns from time to time, providing an opportunity to buy these compounders at reasonable valuations when they sell off along with the broader market.

With traditional value investments, if you find one that works, you have to sell it as the price reaches fair value because the intrinsic value is likely not growing very much every year. Therefore, a portfolio of traditional value investments has high turnover by design, increasing the opportunity to make mistakes.

In contrast, buying compounders is the only investment approach where you can use a buy-and-hold approach, and consider selling only if the valuation gets to an extreme, assuming the rest of the thesis is still tracking.

In addition to trading a lot in college, I completed several summer internships in equity research and investment banking. I did an off-cycle winter project/internship where I worked directly with an analyst at a long/short activist equity hedge fund. I received a full-time private equity analyst offer but decided to start a hedge fund instead.

I started TMR Capital because I believed and continue to believe that I can generate outstanding performance.

We specialize in doing deep fundamental research in SMID caps, which we see as an increasingly neglected area of the market. Our flexible mandate allows us to seek out the best opportunities globally across multiple industries.

We invest in both compounders and traditional value investments, with a focus on GARP investments, value-oriented special situations, and microcap “self-help” situations primarily in developed markets. We target a 20%+ gross IRR while keeping risk under control and seek to deliver uncorrelated risk-adjusted returns from both longs and shorts. To avoid value traps, we underwrite at least a 10% IRR from earnings growth alone – this way, we are not entirely dependent on valuation multiples expansion.

We focus on higher quality, growing businesses where we can identify idiosyncratic corporate situations that offer asymmetric risk/reward such as M&A, spinoffs, management changes, new product cycles, hidden value, underappreciated revenue acceleration and margin expansion.

The current market structure favors long-term fundamental analysis focused on identifying inflection points in companies where the future is likely to be very different than the past. Passive investing is now greater than 50% of equity investing and many value investors have suffered large redemptions or gone out of business. Within active investing, a greater share of capital is flowing to investment strategies with shorter time horizons such as quantitative strategies and large multi-strategy or “pod” shops. Dampening monthly volatility has become far more important than generating “private equity-like” 20%+ returns in the public markets. Therefore, investing based on where you think the earnings power of the business will be even just 3 years out and being able to withstand monthly & quarterly volatility is a huge competitive advantage.

As David Einhorn recently put it: “...in the last couple of years I’ve had the realization that with some of these stocks, nobody’s ever going to care. Nobody’s paying attention, nobody’s doing the work, nobody cares what the company says, there’s just nobody home. So we can’t make money by trying to buy something three months or six months or a year before other long-only investors figure it out because they either aren’t there or don’t have any capital or they’re turning into index funds.”

Since we last spoke, the fund has continued to grow and I now have a full-time analyst. I have also decided to build more in public and launched a Substack available here.

Given your strong track record with tech stocks, do you have any views on AI as an investable theme? Are there any companies you feel are overhyped or underappreciated?

I think the AI infrastructure buildout will continue for years and that we are still early in the super cycle. This super cycle also has the potential to be bigger than previous tech super cycles.

There will be significant ongoing investment in AI hardware, particularly in autonomous and robotic systems, with a focus on onshore manufacturing in the U.S. These will be massive funding deals for hardware buildout, possibly involving government support, to meet the demand for autonomous systems and chips.

Given the scale and impact of AI, we will likely see a massive bubble form around AI companies, which will enable many new entrants into the space. Bubbles always form around transformational new technologies. Valuations will become frothy and many of the new AI companies will fail.

In terms of where we are in the cycle right now and the opportunity set for investors, I think the world will continue to have a compute shortage for at least the next 3-5 years. The aggregate demand this year alone for compute is estimated to be 100 times greater than last year. In fact, there is a good chance that we run out of GPUs, accelerators, and compute this year, similar to 2023. The supply constraints are ongoing and severe.

While I expect there will be fluctuations in demand, as there are in any major technology deployment cycle, the AI investment cycle is durable. The AI use-cases are tangible and with massive reach, including a knowledge worker base of 1.5 B, and large and small enterprises adopting AI.

We are currently in the midst of a massive capex boom in AI acceleration. The competitive drive to build the best LLM — which is a function of data size, data quality, model size and computing power — has led to a demand for ever greater AI hardware/Data Center investments. The market believes that after a surge in AI capex for training these models and for enterprises experimenting with AI, demand will level off. However, after training comes inference, which the market underappreciates, as a much larger source of AI hardware demand. Demand can last for decades with the related inferencing and other computing ecosystem requirements. Inference is critical as it is performed in real-time (i.e, low latency at the prompt or the customer will search elsewhere, for example) in production, unlike training, which is performed as batch processing that can last several days.

Per Amazon at their AWS:Reinvent “for every $1 spent on training, up to $9 is spent on inference.”

Accelerated computing (using GPUs) only has a 2.7% penetration rate:

At just a 2.7% penetration rate, we are on the cusp of one of the biggest data center refreshes in two decades.

Tech giants are demonstrating an unwavering commitment to AI investments, viewing it as crucial for long-term growth and competitiveness despite uncertain short-term returns. For example, Microsoft is taking a decidedly long-term approach to AI investments. CFO Amy Hood stated that their data center investments are expected to facilitate AI monetization “over the next 15 years and beyond.” Google CEO Sundar Pichai emphasized that “the risk of underinvesting is much higher than that of overinvesting.” This sentiment reflects Google's strategy to maintain its competitive edge in the AI race, even if immediate returns are not apparent. Here is Mark Zuckerberg, earlier this year on AI capex spending:

“I think that there’s a meaningful chance that a lot of the companies are over-building now, and that you’ll look back and you’re like, ‘oh, we maybe all spent some number of billions of dollars more than we had to,’” Zuckerberg said. “On the flip side, I actually think all the companies that are investing are making a rational decision, because the downside of being behind is that you’re out of position for like the most important technology for the next 10 to 15 years.”

“If AI is going to be as important in the future as mobile platforms are, then I just don’t want to be in the position where we’re accessing AI through” a competitor, said Zuckerberg, who has long been frustrated with Meta’s reliance on distributing its social media apps on phones and operating systems from Google and Apple Inc. “We’re a technology company and we need to be able to kind of build stuff not just at the app layer but all the way down. And it’s worth it to us to make these massive investments to do that.”

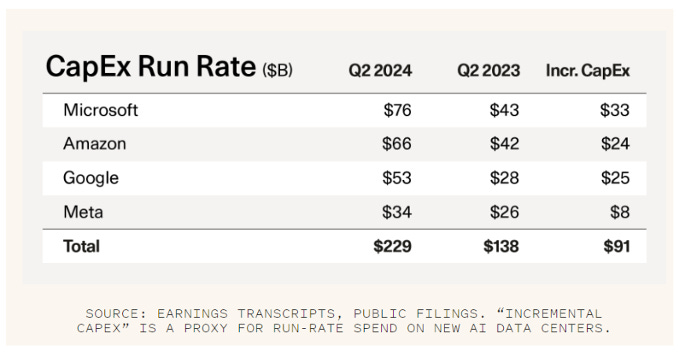

The combined capital expenditures of Microsoft, Alphabet, and Meta grew by 60% year-over-year in the latest quarter, with expectations of 50% growth for 2024. Annualized CapEx for big tech increased from $138B to $229B year-over-year. This incremental $91B in run-rate spending is a good proxy for new AI data center construction—an enormous investment.

Here is a more recent update on AI capex from the hyperscalers by Morgan Stanley:

This is an arms race and none of the hyperscalers and internet giants want to let the others get ahead. We are now in a cycle of competitive escalation between three of the biggest companies in the history of the world, collectively worth more than $6T. At each cycle of the escalation, there is an easy justification—we have plenty of money to afford this. There is a real sense in which only companies that have the balance sheets to withstand big write-offs can now afford to play in the AI infrastructure race. From this perspective, overbuilding may be perfectly rational.

Valuations are also generally reasonable given the tariff dislocation. My preferred way to play this on the long side is to buy traditional value stocks that now have part of their business that benefits from AI. My favorite examples here are: